On a frigid winter day in 1941, a transport truck left Schirmeck for Dachau concentration camp. Among the five Jehovah’s Witness prisoners were Adolphe and the elderly presiding minister of Mulhouse named Huber. An SS guard looked at the white-haired man, pointed to the crematorium chimney, and screamed, “This will be your exit!” Huber, who was more than 60, calmly replied, “It is truly an exit!”

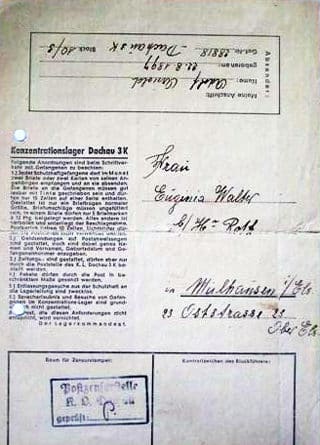

The Nazis offered Jehovah’s Witness prisoners another way out: They could sign a document* renouncing their faith and swearing allegiance to the Nazi state. They would be given their freedom as a reward. But they would also have to agree to denounce other Witnesses to the Gestapo, virtually ensuring their arrest and imprisonment. The Nazis seldom succeeded in getting a signature, even under torture.

Like all prisoners, Adolphe’s had to exchange his identity for a number—28818—and the peaceful artist with gentle hands was immediately sent off to do hard labour in the punishment battalion. He wore the purple triangle of the Bibelforscher on his uniform. The Nazi captors intended the symbol to be a stigma, but for Witness prisoners, it enabled them to identify and support fellow believers. For the first three months Adolphe had no news from home, just unanswered questions to torment his nights: His wife? His daughter? Only on Sundays could he gain a little relief, sharing spiritual thoughts with some other Witnesses, such as Floryn* from Belgium. Finally, he was permitted to write a few lines and receive a short note from Emma.

That winter, a typhus epidemic swept through the camp, and Adolphe ran a high fever. An SS doctor ordered Adolphe to pump the blood-pressure gauge, but he was too weak. The doctor struck him in the mouth and broke his two front teeth, sending Adolphe into a deep coma. When he awoke he found that his barracks mates had all been replaced by new ones. He had lain unconscious for 14 days.

Just then, relief arrived when the camp commandant allowed the prisoners to receive food parcels from home. Emma’s first package contained a bottle of fish oil and some clay. The SS mocked him, saying, “Your wife sent you earth even before you are ready for burial!” Adolphe knew about the extraordinary healing properties of clay and ate a little every day. He made a full recovery.

Those parcels brought even stronger medicine. Emma found a way to hide scraps of paper with excerpts from the banned Witness journal, The Watchtower. She copied the text in tiny print on fine paper, which she rolled up tight and put between two cookies stuck together with honey. The Kapo (a prisoner foreman) handed Adolphe the first parcel, but it was almost empty. When Adolphe ate the lone cookie and found the hidden paper, he understood why the Kapo had warned him that he should not be receiving messages—and he had proof that the man had dipped into the parcel before he handed it over! He wrote back in a few lines, “Thank you for the vitamins!” and “Please keep sending news from Mother!”

A certain SS man came to him privately during a bombing raid on nearby Munich. “What religion is this pilot?” he asked. Adolphe seized the opportunity to tell him, “I don’t know, but one thing is sure: It is not a Jehovah’s Witness pilot!” That SS came to trust Adolphe and asked him to keep guard whenever he was drinking. On Christmas Eve, all the SS gathered around a huge Christmas tree singing “Holy Night.” At the feast in the SS barracks that night, each man stashed his forbidden bottle of alcohol under his seat. The SS man brought Adolphe along and seated him at the table to act as a shield from the eyes of the commandant. Each time the SS leaned over to take a drink, Adolphe had to lean forward to block him from view. During the night, some of the SS would go out and come back with bloodstained clothes, singing even louder, “The divine child is born…” That “privilege” was torture for Adolphe.

The Allies carried out another bombing raid on Munich, which damaged the SS man’s house. He received some new furniture and asked permission to use the prisoner Adolphe to paint it. Adolphe not only painted the cabinets, but he decorated it with Bavarian designs. The SS saw that money could be made from this artistic prisoner. He told Adolphe he wanted to open a business printing scarves and aprons and to have Adolphe work for him. He would have him let out of camp and bring his wife and daughter to be with him. Adolphe was cautiously hopeful at the prospect of getting his family away from the terrible pressure they faced daily.

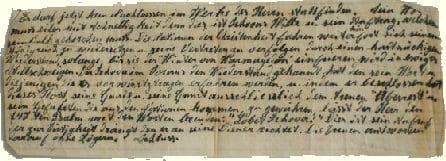

The commandant often summoned Adolphe to the office to hear police reports about his rebellious daughter. Simone kept refusing to heil Hitler. She had been interrogated by the Gestapo and was finally sentenced to a Nazi reform school. Each time he was called, the SS ridiculed or punished him, blaming him for her actions. Still, Adolphe’s heart swelled with satisfaction because he knew his daughter had stood up for her faith. In one letter* he wrote her: “As long as we follow our hearts, we won’t lose our joy, because our heart will judge us. It is this joy that is the best guarantee that our identification of what is good is the right one. It is also the anchor of our lifeboat and will bring us safely through the stormy sea.”

Truly Adolphe almost drowned in that stormy sea. Once more the commandant summoned him to hear that the decision of the Mulhouse court had been applied. His beloved girl had been taken away from her mother and sent to Constance to be “re-educated:” Less than two months later Emma was arrested and sent to Schirmeck camp. Adolphe knew that would be the end of his mail. Regulations forbid prisoners to send letters between camps. The only link to the outside would be Eugenie, Emma’s sister.

Though Adolphe rejoiced that his wife and daughter had stayed true to their faith, he could not lift his spirits at the thought of their captivity. He lost all his strength. Starvation diet, hard labor, constant pressure to sign the document of renunciation, and the knowledge that Emma faced the same left Adolphe on the verge of physical and emotional collapse. One day he stood in line for the shower in that low state of mind. In front of him one man asked another which Bible text the pastor had chosen for him at his Confirmation. He replied, “Trust in the Lord with all thine heart, and lean not unto thine own:” The words were like oil on a wounded heart, like the voice of an angel—just what Adolphe needed to shore up his determination to endure despite what lay ahead. Sure enough, a new challenge confronted him.

The call came again to present himself at the Kommandatur. As he entered, he saw that almost all the SS on duty stood waiting for him. The commandant had received the SS man’s request to take him outside the camp to work. Permission could be granted, but before drawing up the necessary papers, Adolphe would first have to paint pictures of dolls on a large stack of wooden crates. The SS added, “We’re not transporting dolls. It’s ammunition.” Adolphe refused. He would not do work to support the war, and he would not lie, he said, not even with a paintbrush.

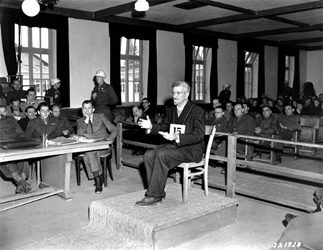

The SS broke out in collective laughter. They would have some fun. One SS pretended to be “Jehovah” and another played “Jesus.” As the paroxysm of blasphemy ran its course, Adolphe could no longer endure it and said calmly in a strong voice, “Please, sir, Jehovah is the name of God Almighty!” They fell totally silent, stiff from the shock as it slowly sank in that a prisoner had dared to correct the mighty SS. “Raus!!” shouted the commandant. Adolphe fully expected to be hanged. Days passed and nothing happened. Yet the matter had not been forgotten. The order came to make him a Versuchskaninchen, a human guinea pig.

Adolphe reported to a special section of the camp, supervised by SS doctors who, like the infamous Mengele of Auschwitz, conducted prisoner experiments. They concluded that this prisoner must have a strong immune system. After all, he had recovered from typhus. He would make a fit subject to test malaria vaccines that could protect German soldiers fighting in the North African theatre. They tied a little cage to his elbow just on top of the vein so that the mosquitoes could feed easily. The cage remained there day and night, with the insects exchanged and vials of blood drawn several times a day for six weeks. The inoculations proved ineffective, and Adolphe was ordered to board a truck transport. Everyone knew what that meant, but just as he was climbing into the truck, the SS man for whom he worked passed by. Then a doctor appeared and called Adolphe down saying they had not yet finished the experiment. He would stay in the infirmary for several more days.