In 1932, the owner of the Wesserling factory unexpectedly put up the business for sale. The resulting staff cuts created an uncertain future, even for the management staff. Adolphe’s reputation had spread beyond the town, and the largest textile printing factory in Pfastatt near Mulhouse, Schaeffer and Company, offered Adolphe the job of lead colourist in their Art Department. It was a hard decision, leaving behind his beloved mountains for the flatland city of Mulhouse. Taking the job would mean an extended period of commuting until a place opened up in the factory-owned housing. But with a wife and child, job security had to be Adolphe’s main priority. They would have to move out of their lovely cottage home to a three-story city apartment house. In 1933, after a year of making the lengthy train commute and spending long hours away from home, Adolphe and his family made the painful move to 46 Rue de la Mer Rouge. Not long thereafter, Schaeffer made Adolphe a supervisor. He oversaw the chemists who implemented his design proposals, and he set the price and quality of the finished product.

The new position required Adolphe to do shift work. When he worked mornings, the whole family enjoyed their evenings together. The doting father carefully checked Simone’s schoolwork and read aloud from his favourite books on history, astronomy, and geography. Emma loved to listen while doing needlework and even their little dog Zita seemed to take it all in while lying contentedly at Adolphe’s feet. The newspaper brought word of labour unrest. Adolphe was sympathetic to the socialist workers movement and avidly followed the news of their demands for social justice. When Adolphe worked the afternoon shift, the family ate their noon meal together, and Simone got to sit on his lap while he had his coffee before bicycling off to work. When he returned home at 10:20 p.m., he would head straight to Simone’s room to kiss his sleeping girl ‘good night.’

Meanwhile, worker agitation simmered and finally boiled over in the great crisis of 1936, culminating in a nationwide strike. Angry labourers barricaded themselves inside the factories and took the white-collar workers hostage, Adolphe among them. Fortunately for him, at Schaeffer a new shift of workers arrived to maintain vigil, including men under his supervision. They insisted on releasing him unharmed, saying, “He may wear a white shirt but he’s really on our side. We have a fine relationship.” The workers knew Adolphe to be respectful and gentle toward them all, even while his ‘yes’ meant ‘yes’ and his ‘no’ an absolute ‘no.’

If Adolphe wore white shirts to work, he couldn’t stretch his salary to buy any. But his cherished and industrious wife used coupons to buy remnants at the factory and made him his shirts. Adolphe believed that only careful saving and hard work could secure his family. When the strike resulted in two weeks of paid vacation, he refused to take it. But the law made it compulsory and the factory had to close. He and Emma had a long discussion about whether or not to take the money from their savings to buy two bicycles to ride in the Vosges Mountains. They finally concluded that the three could save on train fare and go by bicycle more often to visit their families in Oderen and Krüth.

On restful weekends Adolphe delighted in playing outdoor games with Simone or teaching her to paint. Sunday mornings were invariably set aside for Mass. In the afternoon the family took long, leisurely strolls in the nearby meadows. Adolphe led his tranquil household with a firm but gentle hand, and he could not conceive of any other way of living. Suddenly, though, a problem arose with Emma, and what a challenge it proved to be!

During the early spring of 1937, Adolphe and Emma had both seen a priest misbehaving with a young teenage boy. Emma insisted that God would not allow himself to come down in the holy wafer to be presented by defiled hands. Adolphe vehemently defended the Catholic Church as holy, founded on the apostle Peter. Believers must be faithful and should leave the judgment of individuals to God. Emma started attending a newly built Catholic church. Adolphe continued going to his own. A tense air filled the Arnold household as strong disagreements erupted into frequent arguments. The storm was just beginning to build. Later that year, Emma received three booklets from Jehovah’s Witnesses (also known as Bibelforscher, German for “Bible Students,” prior to 1931) and bought herself a Bible to study on her own. Adolphe accused her of being presumptuous for questioning church teachings. He forbade her from involving Simone, now seven years old, in the dispute, and he took his daughter with him to Sunday Mass.

Emma stood up for her right to choose her own reading. This placed Adolphe, who had always believed in individual liberty, in a very difficult position: Her freedom of choice became a challenge to his authority. So he reluctantly gave in. But he retreated into total silence. Hardly eating and sleeping, he smoked incessantly and left the house for long walks with Zita.

Adolphe regularly took Simone with him to church, but his daughter had started asking awkward questions prompted by passages her mother had read to her from the Bible. Nearly a year of silence elapsed when Adolphe decided he had had enough. He was the man of the house, wasn’t he? The family was his responsibility, including the obligation to do everything possible to rescue his wife. He decided to order a book from Jehovah’s Witnesses to expose the sect as nonsense. He chose their book Creation since he was well versed in astronomy. When the book arrived, he left the package unopened for three days.

The blanket of silence in the home became even heavier. Later Adolphe would learn that his discerning wife had ordered their irrepressible daughter to keep quiet while her father thought matters over. He studiously compared his favourite books by Abbé Moreau with the Creation book, and before long Adolphe humbly acknowledged that what his wife had discovered by her Bible reading was true. In his excitement, Adolphe made a special trip to give a Bible to his devout stepfather, never imagining Paul Arnold’s angry reaction. He took the Bible and hurled it out the window, then grabbed Adolphe by the seat of his pants and shoved him out of the house with the words, “You, Emma, and Simone are forbidden to set foot in this house! If you want to come back, we will meet in church, but first you must make confession and communion!”

Emma’s family and then the whole village near Bergenbach did likewise, leaving the Arnolds as outcasts. In town, the neighbours too turned against them when they realized that Adolphe no longer supported the church. One man felt it his right to chase after Adolphe wielding an axe.

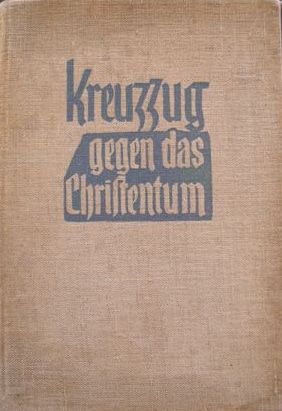

The family’s isolation ended when they attended a public lecture given by one of Jehovah’s Witnesses. There, Adolphe met another Adolphe, Koehl by his family name. He was a long-time Bibelforscher and a top-rate barber in town. As a regular barbershop client, Adolphe found a close friend and devoted colleague in Adolphe Koehl. Through him the Arnolds learned about the book Crusade Against Christianity, which carried firsthand reports of the terrible oppression suffered by Jehovah’s Witnesses in Nazi concentration camps. Their endurance and faithfulness to Christian principles, even in the face of persecution and death, fired the Arnolds’ determination to embrace their stalwart example.