Students ‘Meet’ Holocaust Survivor

By Tim Ashley Posted

With Permission of The Mail Journal

Skype brought all the Leesburg Elementary sixth-graders together with a Holocaust survivor from France Tuesday morning.

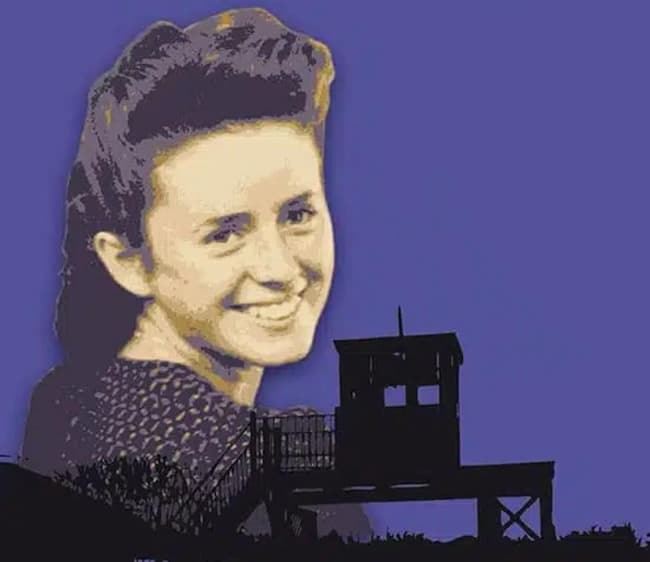

Simone Arnold Liebster was born in August 1930 in a small Alsatian village. She and her parents became Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Because of their faith and refusal to conform, the Arnold family was persecuted, beginning when Simone was only 11. She was taken to Germany and put in a Nazi penitentiary home. Her parents had been imprisoned in concentration camps.

At the end of the war, however the family all returned home and rebuilt their lives.

Simone attended art school. After learning English, she traveled to the United States to the Watchtower Bible School of Gilead. In 1956, she married Max Liebster and together they created the Arnold Liebster Foundation. She now lives in France.

Kristi Keller, Syracuse, a volunteer with the Foundation, previously notified Leesburg about some of the opportunities the Foundation offers like Skyping with Simone. The sixth-grade teachers jumped at the opportunity.

During yesterday’s Skype session, twenty students and one teacher had the opportunity to ask Liebster questions about her experience.

Christina McLaughlin asked, “As a young person, how did you have the strength and courage to stand up and stick with your beliefs?”

Liebster answered, “The strength comes from a relationship with God.” She said it was because of her love for Him that she was able to get through it.

“What’s your worst memory about the Holocaust?” Jannica Seraypheap asked.

“It was the day my father was arrested,” she responded “It was unexpected.” She continued that they didn’t know where he went, and she was only 11 at the time of his arrest. There were many other emotional days, but that was the worst for her personally.

Kevin Mears asked, “Did you make or have any friends when you were at the juvenile home?”

“Impossible!” she indicated. “Because you didn’t have the right to talk. You can’t make friends just by looking at them . . . We had to stay by ourselves.”

Kaden Atkins asked Liebster what it was like for her mother and father in the camps. She answered that her father had a very bad time in there. He wouldn’t deny his faith so he was severely punished. He also was medically experimented on, and lost his hearing. “My parents really suffered a lot,” she said.

“If you saw Hitler today, what would you say to him?” Jose Alvarez asked.

“Nothing,” Liebster answered. “He doesn’t deserve a word. I would look into his eyes.”

She said it wasn’t Christian to retaliate.

“You don’t talk to a dog. So that’s what I would do. Silence,” she continued.

When Dara Hatch asked her if she hated the people that did those things to her and her family, Liebster said there is no reason to hate people. You hate things and actions, but you don’t hate people. She would never do anything or say anything to retaliate, but would show them the way through the Gospel.

Makaela Whitfield asked her if she ever thought about breaking out of the juvenile home. Liebster said that was never a possibility.

“No one could ever escape. If someone did escape, the Germans would kill their whole family as hostages,” she said.

Darian Olinger said he is handicapped, “so do you know what my symbol would have been?”

“There were no symbols because they gassed them and killed them,” Liebster answered. ” . . . I feel very bad to tell you that because I know it hurts you.”

Some of the symbols Nazi prisoners wore as badges included a red triangle for political prisoners such as liberals; purple triangle for Bible students, primarily referring to Jehovah’s Witnesses; pink triangle for sexual offenders, mostly homosexual men; and two superimposed yellow triangles for Jews.

“Did you ever think you would survive all that was happening to you?” Juan Calderon asked.

“When I left my mom, we talked that we may never see each other again,” she said. They also talked about the Resurrection, but it seemed impossible they’d get to be together again.

Dylan Jones wanted to know what her parents were like before and after the concentration camps and how did their personalities change.

Liebster said their personalities had changed for sure. When bad people do bad things to you, she said it closes off your heart for awhile.

In the camps, you had no right to do anything if you weren’t given permission.

After reuniting, Liebster said she and her mother were standing on a street corner waiting to cross the street. But they just stood there for a long time even after it was their turn to cross because no one gave them permission to cross the street.

“Eventually, Mom realized we had to take our position,” she said. “We had to learn to be independent again.”

Deyguer Ortiz asked her if she wished that she could have had a normal life when she was a young girl.

“What do you call a normal life?” she asked back.

In war time, no normal life exists. There’s pressure from everywhere.

“I knew exactly what could come to me if I stood up for I believed,” she said.

However, now she’s happy and her conscience is clear.

For more information about the Arnold Liebster Foundation, visit its website at www.alst.org.