German forces skirted the Maginot Line and stormed into France in June 1940, retaking the formerly German Alsace with a vengeance. Emma feared that war shortages would severely impact city life. Her sister Eugenie planned to take refuge in the village of Oderen. Emma asked her sullen sister to take Simone along and bring her to Bergenbach. At seeing Simone, her grandmother could not forget the Arnolds’ abandonment of her beloved church. She reviled Simone as a child of the Devil. Simone packed her few things and ran away to her aunt’s apartment in Oderen. The painful conflict convinced Eugenie that she had to buy a Bible to prove to Emma the error of her ways. Instead, her reading led her to conclude that her sister had taken the right path and that she would do the same. With the German occupiers already launching violent persecution against Jehovah’s Witnesses, such a decision called for strong faith.

The Witnesses in Mulhouse had already set up an efficient underground operation. Adolphe teamed up with another exceptionally courageous man, Adolphe Koehl, a barber in Mulhouse who was a long-time Witness. Small groups held secret meetings in private homes, moving from place to place to avoid betrayal. Adolphe held regular discussions with several Bible students, a perilous mission indeed. Emma feared for his safety but never showed her emotions and encouraged him in every way. Going out at night was an extra challenge. Blackouts had been imposed because of air raids, and Adolphe could suddenly stumble on a civilian or military patrol. The eyes of Nazi spies were everywhere, ready to denounce families with suspicious behaviour. Secret informers spread throughout the occupied regions with their ears against the doors, anxious to catch those who dared to listen to a foreign radio broadcast or speak disparagingly of the Führer. “Watch out! The walls have ears!” it was said. In that hazardous situation, the biblical injunction to be “cautious as a serpent” certainly applied.

The Germans set up a 3-km (1.8-mile) wide restricted zone to prevent unauthorized movement in the Vosges Mountains that formed the French-German border. Families living in that area had to carry papers proving their residency. Emma took up mountain climbing in that zone, but not as a hobby. She and Simone accompanied Adolphe Koehl on the first Sunday of the month to a small lake surrounded by boulders and caverns. It made a perfect hiding place for a secret rendezvous. A French Witness sneaked across the border and hid a banned Watchtower magazine in a designated cave, and the mountain climbers would retrieve it. Simone insisted on carrying the contraband in a secret girdle her mother had made. On one trip the German border patrol found the three outside the permitted area. They arrested and searched Adolphe and Emma thoroughly, but since it seemed unnecessary to search a young girl, the “hikers” escaped without incident.

The barber Adolphe Koehl and his wife Maria became extremely close friends of the Arnolds. They would meet in the barbershop or in the Koehl’s garden house, where they could speak without the risk of spies, and they could hide some papers away safely.

The Gestapo Arrest Adolphe

Adolphe had the morning shift and would be home for the family meal at 2 p.m. Emma was in the kitchen cooking when the bell rang, so she sent Simone to open the door for her father. The next thing she heard was a sharp “Heil Hitler,” followed by a menacing Gestapo order to Simone: “Go to your room!” Emma came from the kitchen and faced the two men who had entered and sat down uninvited. They ordered her to sit in a chair opposite the main interrogator, a small, nervous man. The other sat in the corner, taking notes on her answers and repeating questions when her answers failed to satisfy him.

Whom does she visit? Who is the person who came yesterday? Where are the meetings held? Does she have banned Jehovah’s Witness literature? Hand over the names of other Witnesses. And so on. They intended to force her to betray her fellow believers. Three hours of interrogation had passed when, under pressure, Emma listed some names. But they were not members of the Mulhouse congregation. They were members of the Witnesses’ Swiss office. The Gestapo angrily slammed shut his notebook. “You are a cunning creature!” One of them said, “If you want to see your husband again, remember: he is in our hands.” The other screamed sarcastically: “Come and see us! You and your daughter will have the same fate. We’ll be back to arrest you!”

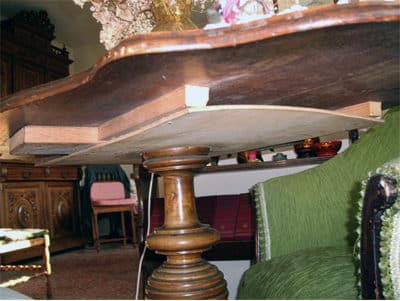

After the men stomped down the stairs, Emma immediately went and took Simone in her arms and said a prayer, trying to calm her own emotions. No use to make things look worse. From that day forward, she and Simone slept together so that her daughter felt safe and at peace. It gave her the chance to have intimate talks and to instill in her daughter the desire to please God above all, to grow in faith, and to lean on the wise counsel of the Bible. Emma rearranged the furniture to stop Zita from sitting in front of Adolphe’s empty armchair and howling. She bought an inexpensive pedestal table with one leg in the middle. She took off the tabletop, sawed a few inches off the leg, built a shallow plywood box, open on two sides, and attached it between the leg and the tabletop. It would provide a place right in the open to hide Bible literature.

Adolphe had been arrested on payday, and the Gestapo had confiscated his monthly salary. At the bank the clerk told Emma that the police had frozen the Arnold savings account. The employment office refused to give her a working card, denying her the right to get a job. The man treated her as “vermin” not fit to work. The realization dawned on her that the Gestapo had maneuvered matters so that she was totally without a means of making a living.

Brotherly Support

Emma faced her dreadful future with courage. Life at Bergenbach had equipped her to face extreme poverty. She had learned from her mother never to give in, and her own deep faith gave her the strength to cope. The Koehls responded quickly, offering the necessities. Emma was grateful for their generosity but refused to live on charity. She arranged to mend the barbershop towels, now irreplaceable because of war shortages, and she would knit socks, sweaters, and even dresses for Maria Koehl.

Emma felt no shame in going on foot to the prison each week, carrying a bundle of clean underwear for Adolphe and bringing his soiled laundry back home to be washed. Anyone on the street knew where Emma was headed at a certain day and time. She never dared to hope she would see Adolphe or to get any news or a letter. One day she tried hiding a small Bible in his bundle. The inspector discovered it, but fortunately for her, the guard was not an avid Nazi, and he merely warned her not to try smuggling anything in again.

A few days later, she was stopped on the street by a prison guard who had formerly been a tapestry maker. He had done some work for the Arnolds in the past. He said he had moved Adolphe to a better cell with a window to let in daylight. He also had gotten him the Bible from the prison library. Emma brought the comforting news home to Simone and told her and other friends how Jehovah had even used non-believers to give spiritual support to his Witnesses.

With the Gestapo keeping close watch, Emma drastically reduced her contact with friends. The Gestapo had returned several times to search the apartment and each time had left without incriminating evidence and without arresting Emma. She visited the Koehls at their shop or their garden house on Monday afternoon. On Sunday’s her sister Eugenie came to Dornach. Emma asked others not to come, for the Gestapo would surely follow. One exception to their isolation was Marcel Sutter, the 22-year-old who had been baptized as a Witness only a few days before Adolphe’s arrest.

Marcel’s attachment to Adolphe and Emma outweighed his fear of arrest. Adolphe had become like a father to him, and Marcel in turn had become a big brother to Simone. He insisted on coming several times a week to check on Simone and to help her with her homework.

Since Emma could not afford to continue Simone’s piano lessons, he insisted on paying for them. But his main reason for visiting was much different. He missed his deep Bible discussions with Adolphe. When Adolphe and four other male Witnesses were imprisoned, the Gestapo thought they had put an end to the leadership of the Mulhouse congregation. Marcel filled the gap and took the lead in the underground work. He asked Emma if they could continue having discussions together, so that he could build on the Bible research he and Adolphe had done.

Though he had only recently become a believer, Marcel had a burning desire to carry on the evangelizing work. Emma worked to deepen his profound love of God. His self-sacrificing Christian spirit brought real comfort to her and Simone, especially since they suffered without any news or word from Adolphe.

… But Family Rejection

The mailbox sat depressingly empty. A single letter had arrived a few days after Adolphe had been taken away. It was from his stepfather Paul Arnold. He wrote how proud he was to be German again, that his grandson Maurice had volunteered for the German army, and that Maurice’s sister was serving German soldiers. He was happy to know that his stepson had been imprisoned, and if Adolphe did not change, he deserved to be sent to a concentration camp! He was happy that Germany would cleanse itself of all its enemies, including the Bibelforscher. For that goal, no price was too high. The letter was signed: Paul Arnold. Heil Hitler!

The letter stabbed Emma’s heart like a sword. The shock caused her chest pains and shortness of breath. She lay on the couch, with no strength to write a reply. Simone was furious. She picked up a pen and wrote: “Your letter is written by the Devil himself!” Emma let her mail the letter.

But then Emma again got a hold on her emotions. Prayer, Bible reading, and sharing her hope with others gave her strength. She had long talks with Simone, careful not to add to Simone’s anxiety and pain of heart. Emma talked often of Adolphe with pride, how he set an example of faith for them to follow. Simone should not worry because they had no mail from him. Soldiers at the front often couldn’t write either. Thousands of families faced the same situation.

News from Dachau

Finally, in December 1941, more than three months after Adolphe’s arrest, his first letter arrived. He had been transferred to Schirmeck, a transit camp in Alsace. After another four months, another letter arrived, this one from Dachau concentration camp.