Emma was born April 17 1898 in Strasbourg, the capital city of Alsace, to Marie and Andreas Fiorvante Bortot. She had her mother’s light complexion and blue eyes but her Italian father’s jet black hair. The impending birth hardly seemed reason to rejoice. Her unmarried mother Marie lived on the mountain farm at Bergenbach with her loving father, Wegerich, her stepmother, and two half-brothers. With the baby on the way, Wegerich felt compelled to allow Marie to marry the baby’s foreign-born father and let her escape life with her alcoholic stepmother.

So Marie, Emma’s mother, left the mountain farm at Bergenbach in search of a happy home and a better life. A life of gloom awaited Marie—three children in four years of marriage and her husband’s constant moving in search of work. Though he was a skilled mason, the local villagers saw him as an outsider and only gave him day work.

The family came to Pfastatt-Mulhouse with the prospect of a longer stay. A growing industrial city offered opportunities for Andreas to use his skills in ornamental stonework. Eugenie, the youngest child, had just been born when her brother died of diphtheria. Four-year-old Emma had nursed her little brother and was inconsolable. Soon thereafter a mason came to the door with the tragic news of Andreas’s deadly accident. He had been working on a stone ornament under the eaves of a roof when the scaffolding collapsed.

The tragedy left the 25-year-old widow and her two fatherless girls stranded in an unfamiliar place. All alone, without work or income, Marie decided to return to Bergenbach, ready to face her stepmother and the villagers’ malicious remarks. Marie set out with Eugenie in her arms and Emma holding her apron tightly. She had to cross through the whole village of Oderen to climb the path to Bergenbach. Her father Wegerich threw open his arms at the sight of his beloved daughter.

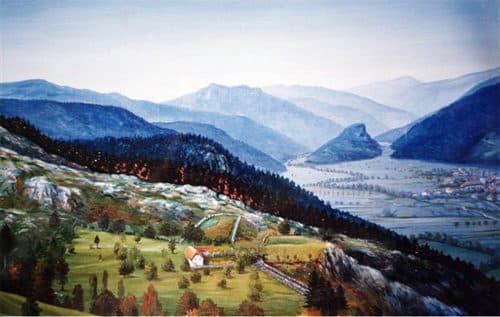

The Bergenbach farm rested on a wonderful spot high up in Oderen Mountain. What a change for Emma, the little five-year-old city girl! The pristine peace of the surroundings failed to penetrate the dilapidated, filthy interior of the primitive house. Marie became a slave once again, herding the cattle, planting the garden, and cooking the meals for seven. The daily chores never ended, and she barely had time for her own children.

The Steadfast Child

Marie’s half-brothers had grown into two boisterous teenagers who considered themselves as having sole rights in the house. They made it clear that Emma was not welcome. Stigmatized by the Oderen villagers and by her mother’s half-brothers, Emma learned to be headstrong. She saw her younger sister as her responsibility and became Eugenie’s protector. Marie was relieved that Emma cared for the baby; still mother and daughter hardly felt close to one another. Emma resembled her Italian father in so many ways that just looking at her flooded Marie’s heart with bitter memories.

Emma felt no more accepted at school. She came down from the mountain dressed in rags with wooden clogs on her feet, soaked to the skin if it rained and gasping for breath if high snow drifts had blocked her way. The schoolteachers were nuns. One of them seemed to notice Emma in class only when she needed a maid. One day Emma had to hold a sheet of music up high while the nun played the violin. After a while, Emma’s hands started shaking. The irritated teacher hit her on the head with the violin and broke it, which only made it worse for the little outsider with the foreign family name.

The death of Marie’s stepmother brought no relief from her deep poverty. The mountain farm scarcely fed the family. Whatever milk, cream, and butter the cows produced had to be exchanged for essentials, such as bread, sugar, oil, shoes, and clothes.

A New Family

A courageous young man named Remy Staffelbach from Oderen defied the villagers’ nasty remarks and married the widow. He joined their primitive life in the cramped house with a dirt kitchen floor, and no running water or indoor plumbing. Living at Bergenbach meant he had to leave even earlier in the morning to work at the Gros-Roman factory, mixing colors for the textile printery. In summer time, he had to mow the grass before leaving for work. After the long trip home, Remy had to milk the four cows and help his aging father-in-law.

The calm and gentle man was willing to raise Marie’s two daughters. Emma was eight and Eugenie four when Remy became their stepfather. Soon he and Marie added a daughter, Valentine, and two years later a son, Germain. Their father made no distinction between his children and his stepchildren, but the gap between Emma and her mother persisted. Emma was a good maid, never mistreated but never hugged.

The Staffelbachs were overjoyed to have a beautiful baby boy along with their girls, but their joy was short-lived. On baptism day, according to tradition, loud blasts were set off to announce the family’s joy and good fortune. The frightened infant let out a heartbreaking cry that continued on for days. Soon Marie realized that her son did not respond to her voice. The harsh reality shattered their joy: Germain was deaf.

The whole family had to face this new challenge. The special schooling Germain would need was simply out of reach for the poor Bergenbach family. The villagers considered Germain’s deafness as a curse from heaven and found another reason to ostracize the family. In defiance, his parents decided to train Germain themselves. The whole family had the duty to learn Germain’s homemade sign language. After school, Emma had to look after him as he played among the rocks surrounding the farm. When she reached thirteen, she had to go to work, and nine-year-old Eugenie took over supervision of her three-year-old brother.

In the Factory at 13

Emma worked at a cotton mill in the neighboring village of Krüth. She set off early in the morning, taking a steep mountain path that wound through forest and field. Whether in the burning heat, stinging snowstorm, pouring rain, or icy winds, she made the long and solitary journey six days a week. She spent long hours standing at the weaving machine. When she returned home, her farm chores still awaited her. At thirteen, Emma was considered an adult.

On Sundays, the devout Catholic family attended church without fail. They were organized so that all attended at least one Mass. Marie and Emma took turns going to early Mass so one could start cooking Sunday dinner while the rest, including Remy, attended the midmorning Great Mass. The children sometimes returned to church later in the day for evening prayers.

Emma had dipped her burning feet in a cold mountain brook and soon came down with a high fever and painful inflammation in her joints. Her mother knew a great deal about natural cures and herbs. The neighbors always called on her for help in emergencies, even for difficult childbirths or animal births. But nothing relieved Emma’s pain. Her hands and feet contorted, crippled beyond use. Emma had to spend six weeks in a hospital to be treated for rheumatic fever. Even the recently discovered aspirin did not help, and the doctors told Marie that they had done all they could and that they had no hope for the girl. They said Marie should take her daughter back home and to expect her to die before long.

Marie refused to give up. She spread a featherbed on a woodpile and carried Emma out every day to lay in the sun, wrapped in another featherbed under the shade of an umbrella. She gave her only buttermilk. In the heat of the sun, she sweated until her whole body was soaked, bringing her relief. Marie poured her strength into the gruelling routine for days on end. Finally, Emma’s fever broke, the cramp in her hands eased, and her ankles firmed up so she could learn to walk again.

Too Poor for the Convent

After her recovery, Emma told her mother she wanted to become a nun and go to Africa as a teacher, a goal that her mother heartily approved. Marie presented her daughter at the convent. They learned that they would have to pay a fixed minimum donation for Emma to enter the convent to become a nun. To receive teacher training, the required donation was even higher. All four cows would have to be sold to pay the price, and even at that, the nuns could not guarantee that Emma would be given access to the special educational program. So the convent door closed on this hopelessly poor girl from an obscure family, leaving Emma bitterly disappointed.

Marie responded quickly. If Emma wanted to do charitable work, she may as well invest her energies in her brother, Germain, who had been deprived of extra schooling by their poverty. Emma had to continue working in the textile mill despite her disability. Her fingers were all but numb, her hands were deformed, and she had chronic shortness of breath. The factory owner took her back, but because of the condition of her fingers, he gave her a different job. She learned to tie spools of thread together, which was excellent therapy to restore the dexterity in her hands.

In the Torments of World War I

Emma had just gotten her sister Eugenie, then 13, a job in the mill when World War I broke out. Shortages of cotton, along with many essentials, soon followed. All the young males in Alsace were considered as German citizens and were drafted into the German army. The French army overran the German border, which crossed the summit of Bergenbach. When the battalion commander saw the location of the farm, he decided the site would be ideal for his headquarters. The house stood well outside the range of enemy fire. French soldiers ordered the family to vacate their rooms and move into the adjoining hayloft. The soldiers ate their own food rations at first, but the supply lines soon dried up. They started eating the chickens and rabbits, and then slaughtered the cows one at a time, hardly sharing anything with the family.

The Staffelbachs, who only spoke Alsatian (a German dialect), were treated as virtual enemies. Their two beautiful Italian daughters faced the constant threat of rape by French soldiers, especially 17-year-old Emma. As the war raged on, the wounded began pouring into the valley. One by one the schools were converted into hospitals. Oderen’s hospital was crammed with wounded soldiers, both German and French. Marie seized the opportunity to send Emma to the relative safety of the village. She could assist the nuns at the hospital and have a safer place to sleep.

Emma did what she could to help soldiers from both sides during the long years of the war. The wounded—French and German—were carried from the nearby battlefield, their bodies slashed to ruins by enemy bayonets. And there they now lay, sobbing in anguish, united by their common misery. Emma bravely cleaned the dirt-covered bodies, assisted with primitive surgery to close the wounds, and then changed the blood- and pus-soaked dressings. She spent herself totally as long as the stream of wounded came in from the battlefield they dubbed “the Verdun of Alsace.”

Marie decided to send Emma far away for a few weeks to a distant relative to learn how to sew for the family. As poor as Marie had been her whole life, she always paid attention to her appearance. She decided that Valentine would have a different childhood, better than her two sisters. She had toys and no chores that would ruin her soft white hands. She wore pretty dresses, sewn by Emma. When Valentine went with her father Remy to Great Mass, everyone in the village looked at the Staffelbach family with respect.

The Bergenbach farm had indeed proven to be safe from artillery damage, but it took years to replace all the plundered livestock. Emma and Eugenie had regular work in the cotton mill. Eugenie was still an apprentice, but Emma was old enough to receive regular wages, which she turned over to her mother for Germain’s schooling. At age 13, Germain was finally able to attend a school for the deaf, run by nuns in Strasbourg. They could only afford to send him for two years at boarding school, during which he learned to read the alphabet, to say a few French words, and to make some simple signs. They taught him the catechism and many prayers in French. Back home at Bergenbach, Germain reverted to his own sign language. Everyone else in the family had only gone to school during Germany’s control of Alsace, but at least Emma had learned some French while she worked in the hospital, so she could understand when her brother spoke. As a consequence, the two became very close.