That summer of 1944, Adolphe was put on a regular transport to the most dreaded camp in Austria: Mauthausen.

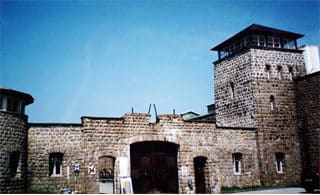

The prisoner transports were more like cattle cars, and the arrival at the camp continued the dehumanizing process with shouting, threats, and humiliation by the SS guards. The painful shaving and delousing treatment added to the torment for Adolphe, who was marked by a new number—89033—and block assignment A.K.P.U. Mauthausen sat perched on a hill of granite. The long uphill walk to the camp was a physical drain on the prisoners but a greater psychological shock. Built by prison labour to resemble a Middle-Age fortress, its towering stone walls hid the camp from the sight of passers-by.

Neither could the dreadful stone quarry be seen. A granite stairway of 187 irregularly hewn steps linked the stone pit below to near and far building projects above. In double time the prisoners had to carry massive stone blocks on their backs. If a prisoner fell, he had no chance to survive the human wave that trampled him to death. Those who could not keep up the pace would be kicked back down the stairs by the SS guard, taking down other prisoners with him. If a prisoner somehow got to the top of the stairway without his stone, the guards took him to the edge of the cliff and gleefully shoved him off the “Parachute Wall” to his death. The terrifying sight of hanging corpses reminded each one that this too could be his last day.

It took a mere three months to exterminate a prisoner by hard labour. An assignment to the stone quarry spelled a virtual death sentence. Adolphe grew weaker and weaker. Had it not been for the help of other Witnesses working in the quarry, he would have met a rapid end. A “purple triangle” named Mattischek* worked as a stone mason. When he could get away with it, he cut and set aside “lighter” stones for certain prisoners.

Amidst the horrors of Mauthausen, even more than in Dachau, survival depended on good relationships. Witness prisoners bonded tightly to sustain each other’s physical and spiritual life. They secretly gathered on Sunday afternoons behind the last barrack, where only two watchmen were needed to stand guard while they read together from prohibited pages of the Bible. No one had news from the outside, nor any mail, nor external contact of any kind.

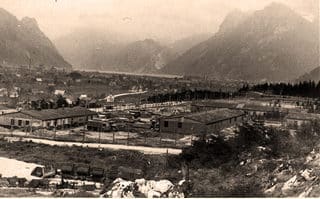

That winter, food shortages in the camp intensified because of the war, sending the already horrific death rate soaring. Adolphe was faltering. He knew he was facing his last days when an electrician with a purple triangle noticed and came to his aid. Eugen Schwab* had been in camp since 1936 and had been granted certain privileges, including the right to move freely about the camp without a guard. He managed to get Adolphe out of Mauthausen and into the sub-camp of Ebensee. He knew that the living conditions in Ebensee were even worse, but at least Adolphe would be out of the sight of that sadistic bunch of SS standing on the stone steps like jackals waiting to send their prey scornfully over the Parachute Wall. Schwab found a place for Adolphe to work at Ebensee—in the laundry.

Adolphe’s fate lay in the primitive camp deep within the Salzkammergut region of the Austrian Alps. Large numbers of prisoners came from the East, especially from Russia. The camp commandant had already cut the daily food ration in half but decided to reduce it down to a quarter. The winter months and heavy snows wrought even greater desperation. At least in summer the prisoners could find grass or sand to calm their hunger pangs. Soon a black market of stolen meat appeared—it proved to be cannibalism. Adolphe lived in anguish with this knowledge. He was already near death but was terrified of falling asleep, lest he fall victim to those who preyed on dying inmates, cutting off chunks of flesh for the market.

The few “purple triangles” in that camp kept close watch over each other. Adolphe had arrived in precarious health, but his work in the laundry afforded him some protection from the biting cold. In a washing pit filled with hot water, Adolphe had to walk to and fro, trampling down mounds of dirty clothes like a human washing machine. The SS guard barked orders at him while the killer dog paced back and forth in time to Adolphe’s movements. One day the SS ordered him out of the pit. Adolphe had one bad ear, damaged since childhood by scarlet fever, and facing that side, he could not hear the SS order. Suddenly, he looked up to see the killer dog lunging toward him. He jumped to avoid the snapping teeth and slipped on the wet steps. He fell on his bad ear. The SS boot came down on his face just below his eye, crushing the delicate bones of his good ear. He got on his feet and was alive, but he suffered permanent hearing loss as a result of the violent incident.

The former salt mines of Ebensee provided a perfect place for the Germans to build concealed tunnels. The majority of Ebensee slave labourers worked in these tunnels building V-1 rockets. In the closing days of the war, it was rumoured that camp administration planned to herd the prisoners into the tunnels, seal them, and destroy them with explosives. The prisoners determined that when the order came, they would refuse. The few Witness prisoners hid in a barrack and prayed together as the camp descended into anarchy. A hail of bullets left hundreds of corpses scattered throughout the camp when the first American soldiers arrived.

Many surviving prisoners were too weak to walk, including Adolphe. He and others were brought by truck transport to a Red Cross camp in nearby Bad Ischl. There he learned that the war had already been over for a few days! He also heard that according to the Yalta agreement, Russian forces were to have liberated the valley of Ebensee. But an American battalion passed over the agreed-upon boundary of Bad Ischl and reached Ebensee before the Russians.